[Thoracoscopic Surgery] Thoracoscopic Empyema Surgery

Release time: 11 Nov 2025 Author:Shrek

Empyema is a condition caused by the accumulation of purulent exudate in the pleural cavity due to infection by purulent pathogens.

According to its onset and course, it is classified as follows:

(1) Acute empyema: The course of acute empyema generally does not exceed 6 weeks.

(2) Chronic empyema: Emyema lasting more than 6 weeks is classified as chronic empyema.

1) Causes of Acute Empyema:

A. Pulmonary Infection: Suppurative lung infections, especially those near the pleura, can directly spread to the pleural cavity. This is the primary cause of infection.

B. Trauma: Open chest wounds, lung injuries, tracheal and esophageal injuries, etc., can cause empyema.

C. Spread from Adjacent Infection Foci: Mediastinal infections, subphrenic abscesses, purulent pericarditis, etc., can directly erode or rupture the pleura or cause empyema through lymphatic drainage.

D. Hematogenous Empyema: In cases of sepsis or septicemia, bacteria can reach the pleural cavity via the bloodstream, causing empyema.

E. Surgical Contamination of the Thoracic Cavity: Postoperative hemothorax infection, bronchopleural fistula, esophageal anastomotic leakage, etc.

F. Others: Such as spontaneous pneumothorax requiring closed drainage or repeated punctures, secondary infection or rupture of mediastinal teratomas, etc.

2) Causes of Chronic Empyema:

A. Improper Drainage of Acute Empyema: Delayed drainage of acute empyema, improper drainage site, excessively thin drainage tube, inappropriate insertion depth, or premature removal of the drainage tube can prevent complete drainage of pus.

B. Foreign Body: Foreign bodies remaining in the pleural cavity, such as shrapnel, fabric fragments, and necrotic bone fragments, are commonly seen in gunshot wounds and blast injuries, especially blind-tube wounds.

C. Idiopathic Infections: Infections such as tuberculosis, fungal infections, and parasitic infections can lead to chronic empyema.

D. Chronic Infection of Adjacent Tissues: Chronic empyema can be caused by infectious diseases such as costal osteomyelitis, subcutaneous abscess, and liver abscess.

High-risk groups include: individuals with lung or adjacent pleural tissue infections, patients who have undergone chest surgery or procedures, and individuals with weakened immune systems.

Typical symptoms of empyema include fever, chest pain, chest tightness, cough, and sputum production. Patients may also experience wasting symptoms such as weight loss, pallor, memory decline, and general weakness. Percussion of the abscess site may reveal dullness, and auscultation reveals decreased breath sounds. Complications of this disease include pyopneumothorax, lung collapse, chest wall retraction, and scoliosis.

The objectives of empyema surgery are threefold: to ensure lung re-expansion, to remove pus and necrotic tissue, and to remove the diseased lung lobe. When developing a treatment plan for a patient, these three core objectives should be considered comprehensively.

The choice between thoracoscopic and open surgery depends on the patient's condition and the surgeon's skill level. A detailed preoperative medical history and thorough CT scan review are essential. Preoperatively, it is crucial to determine whether simultaneous lobectomy is necessary, the degree of pleural thickening, and the presence of fibrous plaques.

Generally, stage I and II empyema can be treated thoracoscopically, while open surgery is still recommended for stage III chronic empyema. Some professors use minimally invasive thoracoscopic surgery for chronic empyema, but this is not mainstream and its widespread adoption is challenging.

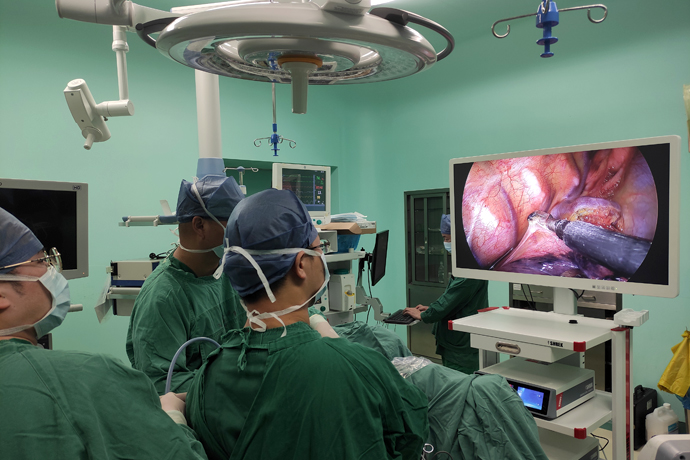

Thoracoscopic surgery differs significantly from traditional open surgery due to the change in field of vision and the use of longer instruments. Surgeons must undergo rigorous thoracoscopic surgical training to master the techniques. Thoracoscopic surgery utilizes large screens and ultra-high-definition cameras, magnifying the surgical field as needed to clearly display minute structures. This provides superior accuracy in assessing the exposure and resection extent compared to traditional open thoracotomy.

Due to its advantages such as less pain, faster recovery, and clearer observation of minute structures, thoracoscopic surgery is increasingly used in thoracic surgery, becoming the most widely performed surgical method.

Whether thoracoscopic or open, the incision can be made in the 5th or 6th intercostal space. If the upper lobe re-expands well and there is no pleural thickening, an incision in the 6th intercostal space is more advantageous for managing lower adhesions. This is because the most difficult part of empyema management is often located near the lower lobe and diaphragm.

Of course, the incision for empyema is not strictly limited. An incision can be made at the lowest point of the abscess cavity to manage the lower part, and another incision can be made in the 3rd or 4th intercostal space to manage the upper part.

Preoperatively, a CT scan is used to assess the degree of pleural thickening and the presence of pus in the pleural cavity. This helps determine the condition below the incision.

If you discover empyema after undergoing closed thoracic drainage, leaving a small amount of pus in the pleural cavity or frequently rinsing with saline solution after drainage will reduce adhesions in the visceral parietal pleura. This will significantly reduce the difficulty of the surgery.

This again raises the issue of surgical timing. After a diagnosis of empyema and closed drainage, the earlier the surgery is performed, the better. Factors limiting early surgery include: the primary condition not allowing it (e.g., acute pneumonia), the patient's physical condition, and other objective factors.

To be fully prepared for potential difficulties in accessing the chest, an operating incision should be made first. After reaching the intercostal space, a small retractor should be used to expose the incision, and the intercostal muscles should be gradually incised, continuing downwards to the thickened pleura. We should have a clear understanding of the situation below the incision using CT scans. In short, the pleura is thickened, and incising it is a necessary step. Care should be taken to avoid damaging the lung tissue; blunt dissection can be intermittently performed using fingers or ovum forceps.

After entering the chest, dissection should be performed first with fingers. If the purulent coating is not tightly adhered, it can be easily peeled off. The area around the operating incision should be cleaned, and then a protective sheath should be placed. The protective sheath should not be allowed to trap any purulent coating, as this will affect the field of vision as we will need to insert the endoscope through the operating incision.

Then, the endoscope is inserted through the operating incision, and dissection is performed using single-port thoracoscopic techniques. I usually add an additional thoracoscopic port at the second intercostal space below the operating port. This port can be further enlarged to handle more difficult adhesions between the lower lobe and the diaphragm. Dissection proceeds towards the planned thoracoscopic port, ideally with thorough cleaning of the parietal pleura in that area, otherwise it will significantly obstruct the field of vision. At this point, the thoracoscopic empyema evacuation officially begins.

Whether it's open or thoracoscopic surgery, once the basic skills are solid, the remaining improvement lies in experience and strategic thinking.

For empyema evacuation, I always prefer to completely free the lung first, regardless of the method, before clearing the purulent coating and dissecting the fibrous lamina.

There's a general standard for lung freeing: the azygos vein arch should be visible superiorly, the phrenic nerve or pulmonary veins anteriorly, and the root of the posterior mediastinal pleura posteriorly. The descending aorta serves as an anatomical landmark on the left, and the azygos vein can be referenced posteriorly on the right. The lower anatomy is often more complex, requiring complete separation of the lower lung from the diaphragm, especially the pulmonary ligaments on both sides, which should be thoroughly freed. The standard is to be able to completely lift the lower lobe. Complete lung mobilization facilitates lung mobility and re-expansion, reducing the presence of postoperative dead space.

This standard also applies to the breakdown of pleural adhesions.

Some details regarding lung dissection:

(1) During dissection, a combination of blunt and sharp techniques can be used. Blunt dissection can be performed using a suction device or oval forceps and gauze. Whether open or laparoscopic, a laparoscopic view should be used for greater safety.

(2) Dissection of the apex of the chest and the superior mediastinum requires particular care and gentleness. Tearing major blood vessels can be fatal. Important structures such as the subclavian artery and vein, phrenic nerve, and superior vena cava must be carefully monitored. Laparoscopic manipulation is strongly recommended. When blunt dissection approaches a blood vessel, the speed should be slowed down. Careful manipulation under laparoscopy is essential. Loose areas can be bluntly dissected using a suction device. If there are cords, they should be cut with an electric hook or a scalpel; blind tearing is not permitted.

(3) When separating adhesions in the lower lobe, begin from the pericardium, taking care to protect the phrenic nerve and locate the interface between the lower lung and the diaphragm. Constantly monitor the diaphragm for damage; if damage occurs, repair and adjust the interface promptly. (4) The attachment point of the diaphragm should be carefully identified and protected. Caution should be exercised when reaching the level of the 9th rib. The attachment point should not be mistaken for an adhesion and cut.

Removal of the pleural lamina fibrousis

(1) Removal of the parietal pleural lamina fibrousis: When removing the lamina fibrousis outside the pleura, special care should be taken to prevent damage to extrapleural blood vessels and nerves, such as the azygos vein, thoracic duct, and esophagus. Above these are important structures such as the subclavian artery and vein, and the phrenic nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve, and superior vena cava on the mediastinal surface. If necessary, important and dangerous locations may be abandoned during removal.

(2) Removal of the visceral pleura requires patience and care. First, use a blade to cut open the lamina fibrousis until normal lung tissue is visible. Then, lift the lamina fibrousis with forceps and use a peanut shell, scissors, electrocautery, or knife handle to remove it from below. If removal is difficult in certain areas, remove as much of the surrounding area as possible, leaving an "island." If the island still affects lung re-expansion, a "well"-shaped incision can be made in the "island." The incision must reach the visceral pleura.

(3) During the dissection process, any lung tissue lacerations caused by the dissection should be promptly repaired with fine sutures using small round needles to avoid omissions.

(4) Instruct the anesthesiologist to inflate the lungs to check for unsatisfactory dissection of the visceral pleura and to check for air leaks in the lungs.

(5) Carefully examine the lungs for tumors, and check for any damage or consolidation of the lung tissue. If the lung lobe cannot be re-expanded, evaluate whether to remove the entire lobe based on the specific situation.

(6) During dissection, it is essential to thoroughly identify and separate the lung fissures.

Preparation before chest closure:

(1) Rinse the pleural cavity thoroughly with warm saline solution to remove purulent discharge and necrotic tissue.

(2) Achieve complete hemostasis. Ideally, use an electrocautery rod, electrocautery hook, or electrocautery knife under thoracoscopy to carefully stop the bleeding in the parietal pleura. Alternatively, apply pressure with a hot saline gauze pad and carefully examine from top to bottom for any active bleeding using a thoracoscope.

(3) Instruct the patient to inflate the lungs and recheck for lung re-expansion and air leakage.

(4) Soak the pleural cavity in povidone-iodine solution for 5-10 minutes. Clean the incision while soaking. Povidone-iodine is a valuable tool in thoracic surgery; it is mildly irritating, oily, and has good permeability. It also has a sterilizing effect. Therefore, povidone-iodine can be used both as a sterilizing agent and as an adhesive. For patients with persistent purulent discharge in residual cavities after surgery, repeated irrigation with povidone-iodine can be used.

(5) Place a drainage tube routinely in the second rib. For the upper drainage tube, a mushroom-tipped latex drainage tube is recommended, as it causes less lung damage and provides good drainage. For patients with pneumothorax, especially those with bilateral pneumothorax and numerous bullae, a mushroom-tipped drainage tube is, in my opinion, the best choice.

(6) Place a 28# drainage tube posteriorly, making several side holes.

(7) Decide whether to place a third drainage tube based on the situation.

(8)All removed purulent coating, fibrous plaque, and other tissues should be routinely sent for pathological examination.

Postoperative Management

(1) Postoperatively, the water-seal bottle should be routinely connected to negative pressure to promote lung re-expansion and adhesion as quickly as possible, eliminating dead space. Generally, the negative pressure connection to the upper chest tube is sufficient.

(2) On the morning of the first postoperative day, routinely perform complete blood count, biochemistry, blood gas analysis, and bedside chest X-ray. Assess for anemia, low protein levels, and whether the lungs have fully re-expanded. Determine whether blood transfusion or human albumin infusion is necessary based on the situation.

(3) Normal saline can be dripped into the upper chest tube for flushing (generally not required).

(4) Control the patient's blood glucose and blood pressure after surgery.

(5) Routinely administer glycerin suppositories on the first postoperative day to stimulate defecation. Ensure the patient has good food intake and regular bowel movements after surgery.

(6) Ensure adequate nutrition. Parenteral nutrition may be added if necessary in the first few days after surgery.

(7) Routinely administer antibiotics postoperatively. Medication should be guided by the preoperative bacterial culture results of blood or pus.

(8) Regularly perform chest CT scans to thoroughly understand the lung re-expansion adhesion situation and check for the presence of dead space.

Postoperative Precautions

Although thoracoscopic surgery is less invasive, it still involves cutting open the chest wall and removing a portion of the lung tissue, which still causes significant stress to the patient's body. Therefore, there are still many things to be aware of after the surgery. The main postoperative precautions are as follows:

Strict smoking cessation: Long-term smoking leads to increased sputum production and weakened expectoration, increasing the risk of lung infections, especially after lung surgery. Therefore, patients undergoing lung surgery are required to strictly abstain from smoking for at least two weeks before surgery and continue this practice long-term after surgery.

Light diet and enhanced nutrition: In the early postoperative period, patients often experience decreased appetite, and surgical stress increases nutrient consumption. Therefore, a light, easily digestible diet rich in protein is essential to ensure adequate nutrition and recovery.

Early mobilization: Surgery and tumors significantly increase the risk of thrombosis. Therefore, unless contraindicated, patients are generally advised to begin early mobilization after surgery to prevent thrombosis, including thoracoscopic surgery. Patients can usually get out of bed the day after thoracoscopic surgery, gradually transitioning by sitting up, sitting by the bedside, trying to stand, and then slowly walking with the assistance of family members.

Deep breathing exercises and coughing to expel sputum: Under normal conditions, lung tissue contains a large amount of air. During lung surgery, the lung tissue on the operated side collapses. Post-surgery, it's necessary to restore the collapsed lung tissue to its pre-operative inflated state—a process known as lung re-expansion—which is a crucial aspect of post-operative lung recovery. This requires patients to actively practice deep breathing and cough promptly to expel sputum, preventing atelectasis and lung infection, and promoting the recovery of respiratory function.

The correct coughing method involves diaphragmatic breathing: take a deep breath, hold it, and then cough deeply. Appropriate pain medication can be used to reduce pain associated with deep breathing and coughing.

Facing Postoperative Pain: Compared to traditional open-chest surgery, thoracoscopic surgery can reduce the degree and duration of pain for patients, but some pain will still occur and recovery will take several months. The degree and duration of pain vary from person to person. Therefore, patients should maintain a positive attitude, believe that the pain will gradually subside, and actively cooperate with treatment and rehabilitation activities. If the pain is severe and unbearable, patients should inform their doctor promptly and use appropriate pain medication.

- Recommended news

- 【General Surgery Laparoscopy】Cholecystectomy

- Surgery Steps of Hysteroscopy for Intrauterine Adhesion

- [Urology Cystoscopy Section] Cystoscopic Laser Lithotripsy

- [Laryngoscopy in Otolaryngology] Tonsillectomy

- [Otolaryngology Otoscopic Section] Excision of Cholesteatoma in the External Auditory Canal